Impact of the Draw in Horse Racing

Unlike National Hunt racing, 99% of flat races in the UK and Ireland utilise starting stalls where horses break out of a designated berth usually chosen at random. Appreciating the integral nature that draw plays in the outcome of race is vital to becoming a long term winner.

Introduction

The impact of the draw can be accentuated or reduced by the pace of the race and the horse’s running style. Below we take a look at draw biases and how perceptions of certain stalls having an advantage can affect the profit for runners from different draws. An insight into how draw and pace are intertwined is then presented.

Draws

With courses coming in shapes and sizes, from flat and straight to undulating and around a sharp bend, each track exhibits varying degrees of bias when it comes to the draw. A draw can help to shape a race as, having a draw that is perceived to be good/bad can influence the tactics the jockey/trainer employ on a horse in the contest.

Chester and Southwell provide two suitable examples.

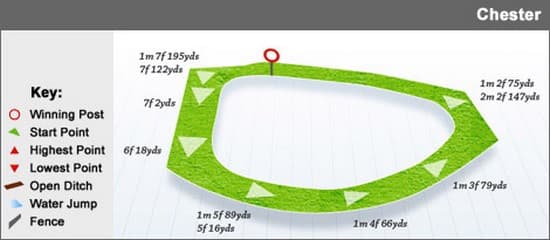

Chester

Perhaps the most well-known bias is at Chester over 5f, where low draws are seen to be at a substantial advantage due to the design of the course:

A very tight oval course with a short home straight is the perfect configuration to produce a bias. Being drawn low, especially over 5f is an advantage as the horses near to the rail have less distance to cover. This draw bias is well known, so it could be assumed that horses drawn low may now be over bet, however surprisingly, it remains a profitable angle.

In handicaps, stalls 1-3 are 79/426 (19%%) over 5f, producing a £32 LSP and winning 24% more often than the horses should do based on odds. Horses on the wide outside have to either cover more ground, or have to use up excess energy to gain a desired early position.

Hold up horses struggle to win sprints due to the short amount of time the horses race at top speed.

Southwell (AW)

Southwell is a course where the perceived low bias is not borne out by the data. This oval all-weather track has fairly sweeping bends and the inside rail often has the deepest and slowest fibresand surface.

Looking at the 8f distance, there is around a 3f run straight down the back straight before the horses reach a bend. This is plenty of time for the runners to adopt their favoured positions without having to use up any unnecessary energy. As the horses on the outside don’t need to get on the inside to be in with a chance of winning, there is no rush or need. Handicaps are the best way to measure draw bias as in theory, all runners should be of equal ability.

The results for 8f handicaps in fields of 10-14 are as follows:

- Stalls 1-7: 218/2905 (7.5%) for a loss of £-895. A/E 0.90. Expected number of winners 242

- Stalls 8-14: 197/2097 (9.4%) for a loss of £-322. A/E 1.10. Expected number of winners 178

High draws clearly have the edge, winning at a higher percentage and winning 19 more contests than the horses odds imply they should. High draws are under bet and low draws are over bet. Low draws have won 24 races less than they should have done.

The media are fairly lazy in their research, and this can be used to the punters advantage.

The high draws win 10% more often than they should do and when finding a horse with good credentials for the race with a high draw, the value of that runner may be compounded.

Draw and Pace

Now that draw and pace have been examined individually, the next step is to gain an understanding of how the two variables intertwine to shape how a race will develop.

When analysing a race and searching for potential bets, it is logical to assess the number of early speed horses in the race first to try and determine what sort of pace the contest is likely to be run at.

As previously mentioned, this can be achieved by looking at prior form and running style when racing in similar conditions, and combining that knowledge with the pace maps that are produced by excellent websites such as Smarter Sig.

For example, if Horse X is a front runner in a 14 runner 7f handicap contest at Kempton, drawn wide in stall 9 you need to ask yourself;

- Are there any other horses who like to lead in this field? Potential competition?

- Are they drawn lower or higher?

- How difficult will it be to cross and lead? Are there many horses who like to race prominently drawn inside stall 9?

- Is there a draw bias over this course and distance? If so how strong is it?

Answering these questions goes some way to solving the jigsaw that is finding value betting opportunities.

Below we use two hypothetical scenarios for the aforementioned Horse X to demonstrate how draw and relative pace in a race can impact upon a runners chances, and can determine whether the horse offers value:

Scenario 1

Assuming that there are no other horses who like to lead early in the example above, and furthermore most of the horses like to be held up, then the opportunity for Horse X to get a preferred race position of leading early, suddenly becomes more achievable.

Horse X is priced up at 8.00 which represents a 12.5% chance of winning the race, when in reality, the horse is more of a 5.00 (20%) shot, as he is likely to get an uncontested early lead, which should negate being drawn wide (a slight negative over this trip).

The discrepancy between the odds on offer and the true odds is likely to be caused to an extent by the draw.

Scenario 2

Horse X is racing in a 14 runner 7f handicap at Kempton, against a field of horses of identical ability to Scenario 1. However, this time Horse X is drawn in stall 3 and there are four confirmed front runners in the field, with the other competition for the early pace drawn in stalls 1, 7 and 14

On paper, this looks like a better opportunity for Horse X to be victorious, as whilst there is other pace in the race, this horse has a ‘perfect’ draw in stall 3 and should be able to take advantage.

This discrepancy is for a number of reasons.

Firstly, Horse X needs to lead to be seen to best effect. There is a horse in stall 1 which is likely to try and bag the rail and go forward. On top of that, stalls 7 and 14 also like to lead and stall 14 in particular will have to be ridden very forcefully in order to negate a wide draw and get to the bend in front, to avoid being trapped wide.

These factors imply that the horses may take each other on upfront and will exert significant energy, going quickly early in the contest.

This has two significant implications:

- Horse X will not be running to maximum efficiency as he will have to race quicker than ideal in the early stages to obtain his favoured racing position, and thus will not have the sufficient level of reserves to finish his race in the desired form.

- With a number of front runners in the line-up and the strong possibility of a fast gallop, the hold-up horses who require a true pace, will be seen to best effect.

Even through the use of a hypothetical horse and race, we are to establish how pace and draw bias (or perceived draw bias) can impact upon the odds and chance of a horse.

Conclusion

The draw bias in horse racing is a factor that should be scrutinised closely before striking a bet. The potential pace in the race and the horse’s preferred running styles should also be considered.

The lesson to be learnt here is to do your own research and do not take what supposed pundits or other punters profess as a draw bias. Going against the grain can often be the most fruitful avenue to take.